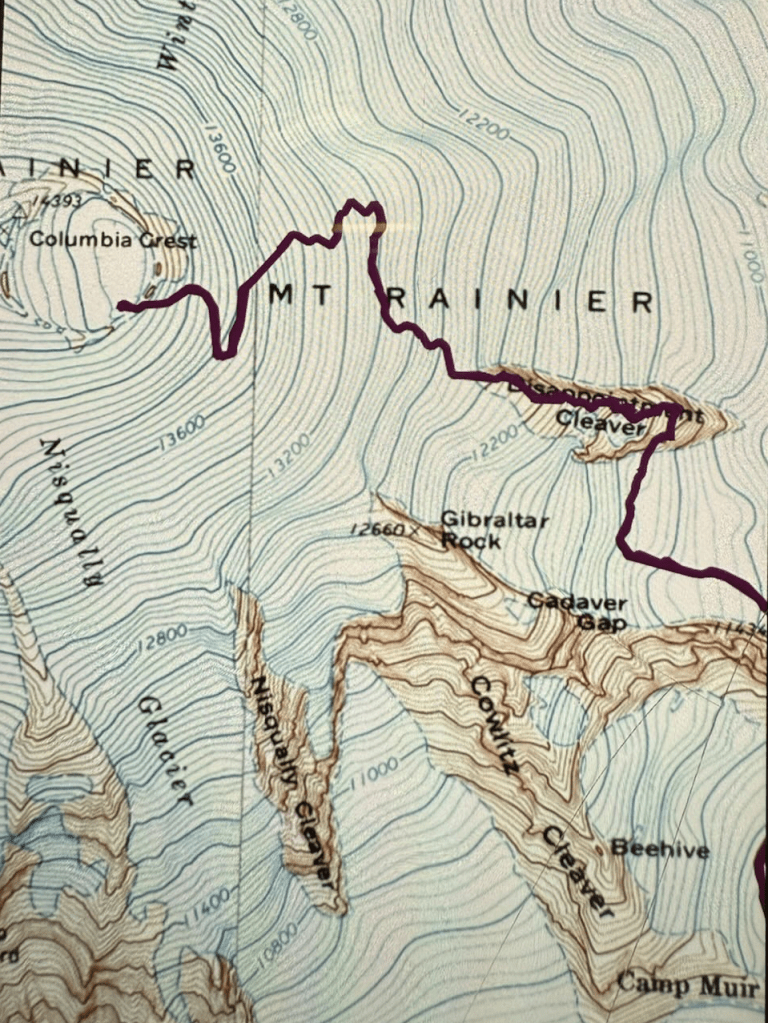

a review of our late-season, single-push climb of Mount Rainier: up the Kautz Ice Route and down the Disappointment-Cleaver

On Sunday, July 27th, Ken and I set out from Paradise, Mt. Rainier, to attempt to climb the Kautz Ice Route up Mt. Rainier in an all-nighter, single push.

We were hyped from our success on the North Ridge of Mt. Baker, a smaller alpine ice climb. We were looking forward to climbing with light packs (not overnight bags) so we could go light and fast up the Kautz and descend the Disappointment Cleaver route, a route I had done twice.

We figured it would take us about 16 hours. It took 28. We suffered, achieved, got a little lucky, and learned a lot in our day-and-four-hour push, from 8pm Sunday night until midnight the next day.

Because it’s important for learning to self-reflect, and it’s beneficial for my business to post about my adventures, the following is a long reflection of the trip. I’ve tried to keep this technical and specific enough to provide some use for climbers, yet generalized enough to still be interesting to those not necessarily seeking to do this next season (hi mom!).

About the route

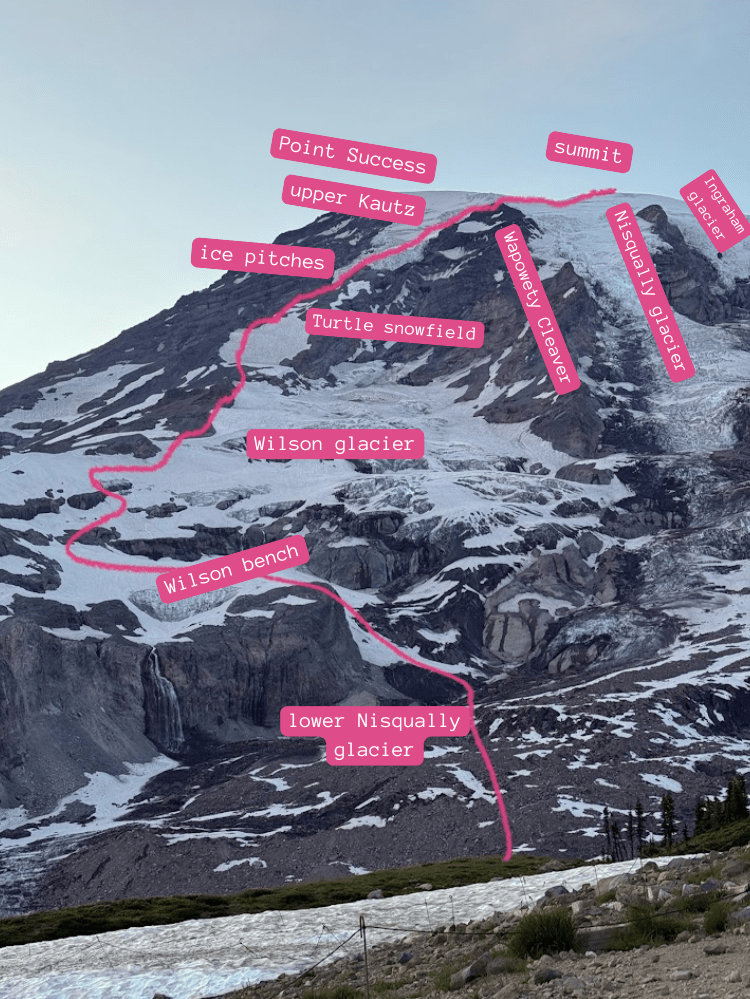

Mount Rainier is Washington’s highest peak, at 14,410. There are three most-commonly climbed routes: the Disappointment-Cleaver route (the “standard” guide route), the Emmons (the popular ski route), and the Kautz Ice Route (with two pitches of alpine ice to climb). It’s best researched with the NPS route brief.

Time plan

Like good little alpine guides, we researched the route, broke it down into legs, asked friends for conditions and beta, and made the following time plan:

| Leg name | Destination | Elevation (ft.) | Gain (ft.) | Estimate duration |

| Paradise parking lot | 5400 | |||

| glacier vista hiking trail | Glacier Vista | 6300 | 900 | 1 hr |

| traverse the lower Nisqually glacier | Bench on Wilson Glacier | 7400 | 1100 | 1.5 hr |

| Ascend the Wilson Glacier | Castle Rock camp | 9200 | 1800 | 2 hr |

| Ascend the turtle snowfield | Camp Hazard | 11,400 | 2200 | 2.5 hr |

| rap a fixed line down a rock step | base of ice pitches (Kautz Ice Chute) | 11,400 (ish) | ~ 0 | 30 min |

| ice climb! | top of ice pitches | 12,00 (ish) | 600 | 3 hr |

| upper Kautz glacier | top of Wapowety cleaver | 13,150 | 1,150 | 1.5 hr |

| upper Nisqually glacier | summit | 14,400 | 1,250 | 2 hr |

How it went

The start

We set out from Paradise at 8pm. We unfortunately had not had enough time that afternoon to take a soon-to-be-much-needed nap, as we had originally planned. We meticulously planned every hour of our route starting from the Paradise lot, but we didn’t carefully plan our summit day starting from when we woke up in Bellingham and drove 5 hours down to Mt. Rainier. Technically, that was part of summit day, too.

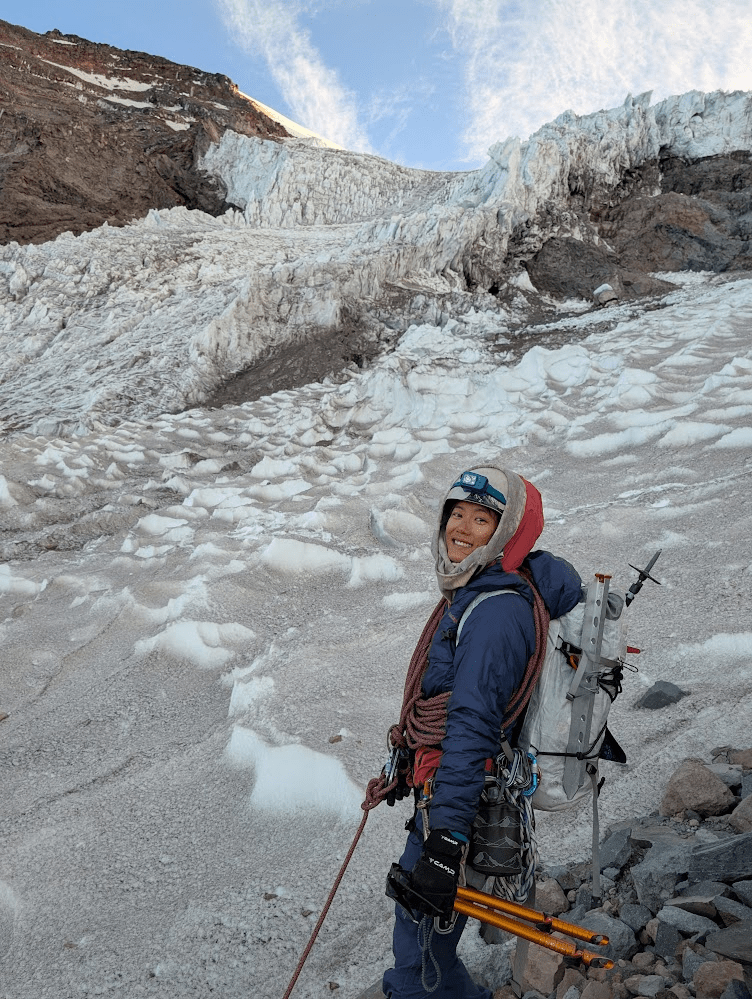

Anyways, a little tired, and later than we meant, we left the van in the parking lot at 8pm. We obsessively took photos of the left side of the mountain as we walked up the glacier vista trail, knowing that soon we would not be afforded such a clear view for navigating.

We briefly debated where to drop down from the moraine onto the glacier (we went up too high at first, following a track that must have been made when the whole slope was covered in snow). At this time of the year, we found a small trail that dropped down to the Nisqually creek, and we walked over rock and thin snow approaching the terminal moraine of the Nisqually glacier.

We found some footprints and started following them, across patches of snow and rock, until suddenly, we noticed a hole underneath the patch of rock, and realized we were now stepping foot onto glacier, just with a lot of dirt incorporated into it. We roped up, and we went about 20 more minutes, to the base of the snow ramp we’d looked at from across the valley, and started ascending up out of the valley, grateful now for all the photos we’d taken, as it was fully dark. This area was supposed to be a big rock fall hazard area, but as the heat from the day disappated, though we walked past and around evidence of rock fall, it felt pretty chill. We traveled well, keeping with our time plan, up onto the bench on the Wilson glacier, and used our headlamps to assess where we would head next.

The night shift

We headed up off the Wilson glacier, searching for the break in the cliff bands. Due to the low snow level, we couldn’t just punch in steps generally going up, exactly where we wanted to, and we ended up doing a couple spicy rock traverses – you know the ones where you’re staring at the front points of your crampons on a pinky-fingernail-sized divot on a rock slab, willing it not to slip as you gingerly step up. It probably felt more exciting because it was night, but I wasn’t too interested in going back down it.

After we got up the brief rock step, we kept ascending the west until we got to the ridge at the western edge of the Wilson glacier.

We ended up at a decision point: keep going on the snow, or move to the rock? The challenge was that snow travel was faster: but from our perspective, we couldn’t see where the steep snow went to.

We spent precious moments examining all our photos from earlier, trying to understand exactly where we were and where we would end up if we went on the snow: would it cliff out? Crevasse out? Were those fuzzy little lines on the snow in our photo from a mile away just a shadow or was that a crevasse? Who knows. We opted for the rock: slower but more reliable.

Walking in the dark behind your partner, following them over loose rocks, attached by 20 feet of rope held in your hand or loosely butterfly-coiled around your shoulders, sliding around, while trying not to trip on rocks is extremely annoying.

I spent precious mental bandwidth managing the rope as it (shockingly!) fell off my shoulders when I moved unexpectedly, or complaining that Ken was pulling me. We lightly bickered and then apologized as we managed the rope and kept stumbling forwards in the dark. We kept thinking that we weren’t going to walk a long enough distance on rock to make de-rigging the kiwi coil worth it. We were frogs boiling ourselves in water.

By this time, fatigue was setting in. Though by this point in the summer, I had absolutely no sleep schedule (1 – 2 alpine starts a week will do that to you), my body still did find it weird that at the end of a 18+ hour day of being awake, we found ourselves still moving and exerting at 1am at night.

We kept walking up this ridge in the rock, hoping to soon arrive at the “lowest paw” on the turtle snowfield (that mountain project comment echoing in my head “do turtles have paws?”) I was hoping we’d finally be in the clear once we could get off the rocks and hop back on the snow. What we didn’t realize was the turtle snowfield, by this point in the season, was steep sun cups. It was like walking up an infinite, inclined, egg-carton: if eggs were the size of bathtubs.

The exhaustion of the all-nighter was really affecting us. We made it up the snowfield and collapsed into a break at the top. Passing rock-circles for camp spots was re-assuring: “look how far we’ve come”, and demoralizing: “we could have been camping, and asleep, by now”.

We kept hiking up, now on rock again, following faint social trails here and there, and a glorious water source that I decided I didn’t want to stop to refill bottles at, because “surely we’ll find another water source up higher” (we did not).

The wind was howling from the east, so we hunkered down in a lovely cave just below Camp Hazard and had another existential crisis. We took a longer break here and acknowledged our fatigue. We had almost pulled through the night. We were also two hours behind on our time plan, but we still felt, upon introspection, that we could do this, and reassured ourselves that having daylight for the ice pitches would be nicer than darkness.

The ice pitches

Dawn rose right as we were searching for the trail to drop down to the Kautz glacier. The little ice step ended up feeling a little spicy, given the usual fixed line had been frozen into the ice and was not accessible. Ken belayed me as I downclimbed and I pointed out key holds and steps while they came down second. We regrouped and prepared to walk quickly across the closer slope, as it appeared there was some overhead hazard, given the rocks scattered across the snow. We walked across and I got prepared to lead.

The ice was amazing. It felt worth the all-nighter approach we had pulled to get here. Super fun, very chill. I was mostly just tired, cardio-wise, due to the fatigue. The Gullys, my ice tools, were great for the low angle ice. I felt quite at home. Ken and I simul-ed the first pitch, making sure we had a screw or two in between us.

We walked long-long-roped across the snow to the base of the second pitch. This one was longer and steeper, a more planar surface, without the nice ledges and features of the first pitch. It felt so different from waterfall ice, even the brittle waterfall ice I’ve climbed, because it was so huge and planar. And it never ended. My calves screamed at me: I probably should have tightened my boots more.

I ended up seeking out the penitentes, because I could stand on flat ice just above them and give my calves a much-needed rest. Unfortunately, sometimes where I took my rests meant that Ken was forced to stop in an un-restful stance (sorry, Ken!) I accepted my defeat and built an anchor at the first little ledge I could find, and belayed Ken up to me. From there, I took off again and we resumed simul-ing for the last quarter or so of the upper pitch.

Since the ice was very convex at the top (like a dome), we couldn’t see how much farther we had to go. I kept thinking “oh this is it, we’re at the top”, as the ice gradually transitioned to snow, the sun cups turning to full body-height penitentes.

The upper mountain

It was full daylight now, mid-morning, and we were around 12,000 feet, above the ice pitches, facing the upper Kautz and upper Nisqually glaciers. We hadn’t slept for 24 hours, and we had around 1/2 liter of water each.

To finish the route, we would have to go 2,400 more feet up and then come down the DC (Disappointment Cleaver) route. I figured that route would fly by, (obviously the faster choice than doing ten thousand V-Threads down the Kautz), so really, we just had to make it to the summit, and then we could come down the DC. That’s all. How hard could it be?

The rest of the route nearly broke us.

The Upper Kautz

It was a fun game, in a way, navigating around the penitentes. My feet are small, and I could dance around them. We started seeing some small-ish cracks. No big deal, we circumnavigated a few. We were switch-backing and zigzagging around penitentes anyways, so it didn’t feel like much of a detour to go 20 meters to the left or right.

Then, they started getting bigger. The words of the NPS route description haunted me: “cathedral-shaped crevasses”. They truly were. They were caverns to the underworld. The actual opening on the surface would only be 10-20 feet wide, but when we’d carefully peer down, we’d realize that the crack was HUGE. It was massive. It was a cavern, and we were standing on the overhung lip. With the texture of the penitentes, we wouldn’t see the crevasse coming, until we were right up at the edge. Fortunately, it was a cold morning and though the sun was out, the snow and ice still felt bullet hard.

Well, after passing a few of these cavern-cracks, we were a little spooked, and less than optimistic about navigating through some big cracks we could see coming up. We decided to bail on this whole “glacier” thing, and hop onto rock. We picked our way over to the Wapowety Cleaver and heaved a sigh of relief when we were once again on solid ground. We tiptoed through the slopes of loose rock, finding our way up a gully in the cleaver towards the intersection of the Upper Kautz and Nisqually glaciers. We were tired but still of the delusion that it would get easier soon: 1,500 more vertical feet to go.

Upper Nisqually to Summit

We arrived at the little spit of rock in between the Kautz and Nisqually glaciers. We’d completed another leg of our trip plan, and now we just had to take the Nisqually glacier to the summit, a summit I’d been up to three times before, so I felt some relief at approaching familiar territory. How long can 1300 vertical feet take, anyways?

At 11 a.m., looking out on the Nisqually, we were intimidated and dismayed. The penitentes were getting taller, and the glacier butting up against this spit of rock was terribly broken up, cracks going in all different directions (swirly, like the eddies at a river’s edge).

We did not see a clear bridge of snow to get onto the glacier, but tentatively, I set out, looking for a way through. What ensued was mentally quite engaging and looking back on it, maybe a highlight of the route. The glacier was not very thick here, but the ice was very hard, which was confidence inspiring.

We tiptoed over snow-blocks bridging 20-foot-deep crevasses (which felt super tame after the cavern-sized never-see-you-agains on the upper Kautz) and finally made it into the middle of the Nisqually glacier. We were about 1200 vertical feet below the summit, 4 hours behind on our time plan, and definitely were not going to turn around now.

But we were in a maze of penitentes. I was in the lead and just started ambling generally “upwards”. At first, though there were some changes of slope, there was continuous snow and it was just a slow slog.

But, upon topping out the next hill crest, I realized we had intersected a giant crevasse. I looked left and right, and it stretched on as far as the eye could see. Shoot.

We were at a cross-roads. Far to the left, there was a way probably to go up the ridge towards Point Success, a false summit, but it looked like the crevasses could be end-run to the right.

We had just switch-backed to the right, however, and travel through the penitentes was so painfully, frustratingly slow, that turning back to the left felt like an exhaustingly bad solution. Surely, this crack had to end soon, we could try to end-run it to the right.

I’ll cut the story short, and say that we had to go probably a quarter of a mile to the right to end-run that crevasse. You can see the diversion to the right. It took forever. It involved going downhill, horrible for the psyche.

We got to one point where the crevasse only looked about 7 feet wide, and I fantasized about placing a picket, lowering in a few feet, swinging over to the other side, and climbing out. It’s a legitimate strategy! Just one I’ve never had to try before, so Ken and I ruled out trying it for the first time on no sleep at 13,000 feet.

Slowly we made progress. By this time, we were really hitting the wall. Every 15-20 minutes we would take a micro break and just collapse in the snow. If I closed my eyes, I fell asleep. I think I slept with my eyes open at one point. We knew this wasn’t good, but we had to keep pushing to get off the glacier. I was sure we were past the turning point, where the way off this mountain was up and over, not back the way we’d came.

We kept eyeing up the final bergschrund. We kept hoping we’d see a bridge as we approached, but instead, we had to traveling far, far to the left, as shown on our GPX track above. We were pretty much above the way we would have gone had we gone left at our decision point, instead of end-running the crevasses to the right on the Nisqually, which would have frustrated us more if we weren’t so exhausted.

We aimed for the saddle between Point Success and the Columbia Crest. In doing so, we crossed the biggest cracks Ken and I have ever seen. In retrospect, maybe we should have belayed each other across these cracks, instead of both being on this massive system of snow bridges at the same time, but we were a bit too tired to make that call, plus, frankly, it was hard to tell what was snow bridge and what was “solid” glacier.

Ken was in the lead at this point, and I just remember being in survival mode, but Ken recalls feeling the whole bridge subtly shift at some point while they were walking across it.

Finally past the bergschrund, we both collapsed into the snow. We’d done it. We had solid snow between us and the columbia crest, about 500 vertical feet away. Navigating from the Wapowety cleaver to the summit had taken 4 hours, to travel 1300 vertical feet.

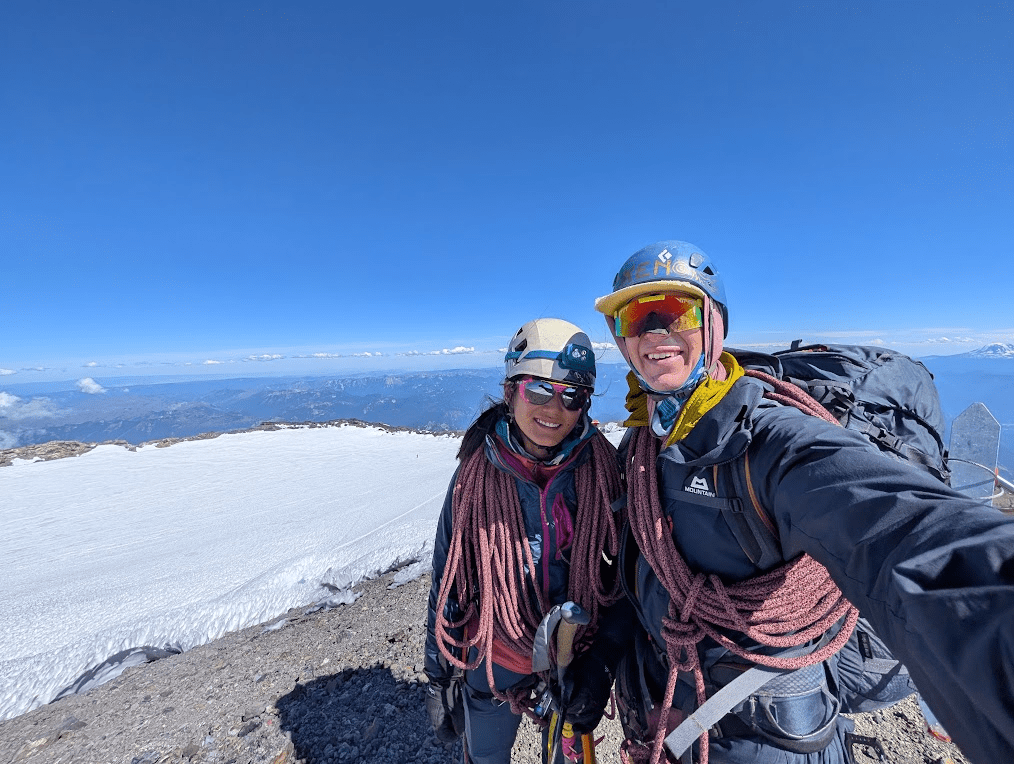

The summit

The most tired summit-selfie ever. 3:50 p.m., 18 hours after leaving the van. I don’t remember much from the summit.

The way down

Descending the DC route was incredibly smooth, just lengthy. The guides had created a re-route basically over to the Emmons, I assume to avoid some big crevasses on the upper Ingraham glacier, but the last thing we wanted to do on our way down was walk uphill towards the neighboring glacier and back.

Fortunately, as it was around 5pm, the whole glacier was in the shade, and the snow was hard, and we had no concerns about snow stability or rock fall, as we might have had, in the full heat of the sun earlier in the day. Somehow, we had managed to be so late that it was beneficial.

The Disappointment Cleaver was completely baren of snow, which meant instead of getting to plunge step quickly down snow fields, we had to pick our way through the traversing rock paths. Fortunately, hiking down the rock and searching for the next little red flag was just the puzzle my brain needed to stay in flow state all the way down to Ingraham flats.

We pulled into Camp Muir around 8p.m. and I’m sure all the climbers we walked past were thinking “where the hell did these guys come from?”, or “you’re just coming back now?”

We re-grouped at Camp Muir and prepared for the hike back to Paradise in the fading light – the second dusk of our trip.

Leaving Camp Muir, I knew what we were in for (endless snow field, then endless hiking trail, then finally downhill pavement in mountain boots on legs too tired to shock absorb the impact). Ken unfortunately thought Camp Muir was “1 hour” from the parking lot and was in for a rude awakening.

Disappointment aside, the way back was peaceful. No one was out (at 10pm on a weekday, shocking), leaving the night air open to all sorts of hallucinations from our tired brains. “Do you hear that singing over there?” “Why are there faces drawn in the dirt?”

We opened our van door in the Paradise parking lot just before midnight and had the best night of sleep all summer. The next morning, we made blueberry pancakes and drove back “home” to the American Alpine Institute parking lot in Bellingham. Over the next 10 days, Ken would complete three Mt. Baker summits, and we would both work 9 of the following 10 days.

Reflections: what we learned

What went well:

Research: We did a lot of route research and prep. We had clearly split the route into legs, complete with notes from different beta sources for easy reference while we were on route.

Contingency/Survival Gear: We also had a strong contingency plan: we’d brought a stove and fuel, bivy sack, sleeping bag, and plenty of extra food. We were prepared to stay the night anywhere on the route, and even considered staying on top of the Wapowety Cleaver, or at a bivy site on the crater.

Ice tools: I brought two Gully axes, bolted and electrical-taped pick weights to the heads (to make them swing better) and it wasn’t half bad! If a pair of Quarks had magically appeared at the base of the ice pitches, I would have happily used them, but the trade off in weight and comfort in my hand was worth it for the rest of the route. The route is a lot of walking, with a short ice section in the middle.

Playing it safe, navigationally: One thing we’d considered, halfway up the Nisqually glacier around 13,500 feet, was traversing east to intersect the DC route, instead of going up to the summit. We opted not to do this, out of concern for getting crevassed out in the unknown area on the upper eastern Nisqually / western Ingraham glacier. We didn’t have a GPX track of the DC route and were worried we’d just waste more time getting lost. I think this was ultimately the right call, but perhaps with more knowledge of the upper DC route, and familiarity in general with the glaciers on Rainier, I’d be more comfortable in the future questing off on a shortcut.

What we will do differently next time:

Sleep: If (a big if) we do another intentional over-nighter like this, we will nap the before! It was pretty brutal heading out at 8pm already a little tired.

Scheduling: We also knew we had work (5 hours’ drive away up on Mt. Baker) the day after we were supposed to finish the route, which contributed to the pressure to finish the route, instead of sleeping somewhere up on the mountain. It was interesting to reflect after climbing, how much I felt this pressure while we were up on the mountain. In the future, I probably won’t schedule big routes like this right before work!

Caffeine: I carry a couple squeeze goo’s of emergency caffeine, but when I needed them most (the whole upper mountain), I was saving them since I didn’t want to run out. I don’t recall having any caffeine the whole trip. I don’t like planning to have to be caffeinated, as a general rule in my life (over-caffeination as a software engineer and computer science undergrad ruined that for me), but for this alpine all-nighter, I wish I’d had like 600mg of caffeine. Ken, on the other hand, ingested enough caffeine to kill a pony, with close to 2 grams of caffeine during our trip.

Consider over-nighting: I’m still on the fence about this one. It was great to carry 30L bags the whole trip. In retrospect, it might have been a lot better if we had hiked up to Camp Hazard on the first day (all in the daylight) and woken up around 3am to do the ice pitches and finish the route. The small amount of extra weight would probably have been worth it.

WATER: We should have stopped at the water source above Camp Hazard. Running low on water and energy at altitude wasn’t smart. We passed up on this water because we knew we had the stove and could always stop to melt water if we needed it, but then later when we should have had more water, we didn’t want to stop to take the time to get the stove out. We’d heard there was water up at 13,000 on top of the Wapowety Cleaver, but if there was running water there, we did not find it. Lesson: if you find water on the glacier, drink it.

Overall

Overall, I’m so proud of Ken and myself for planning and completing this route. Above all, I’m so grateful to the mountain for letting us up and down safely. I don’t want to end up that fatigued again on accident, for safety and enjoyment reasons, but it was some great Type 2 Fun to push ourselves close to that physical and mental limit, especially after so much guiding where we are obviously much more conservative in our risk assessment. We took the lessons from this route with us to our next objective, several weeks later, where we backed down from climbing Mt. Stuart’s North Ridge, but that’s another story.

I’m looking forward to doing this route again sometime, as well as the other routes on Mt. Rainier. Growing up in Seattle, I’ve got an inherent attraction and fascination with the mountain. Here’s to the 5th lap next summer.

Thanks for reading this far! If this post inspired you to get out there, or if you have any questions about the route, leave a comment below or contact me. If you’d like to climb together, you can learn more about me here, and check my availability here.

Subscribe

Follow my blog to have new posts delivered to your inbox.

Leave a comment